Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Article Information

- SUN Yuhao(孙雨豪), CHEN Xiaolin(陈晓琳), LIU Song(刘松), YU Huahua(于华华), LI Rongfeng(李荣锋), WANG Xueqin(王雪芹), QIN Yukun(秦玉坤), LI Pengcheng(李鹏程)

- Preparation of low molecular weight Sargassum fusiforme polysaccharide and its anticoagulant activity

- Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 36(3): 882-891

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00343-018-7089-6

Article History

- Received Mar. 20, 2017

- accepted in principle Apr. 21, 2017

- accepted for publication May. 27, 2017

2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

Thromboembolic disease often affects human health, causing acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, and cerebral ischemic stroke (Pang et al., 2011). Therefore, scientists have developed anticoagulant drugs that are widely used today to treat disseminated intravascular coagulation and thrombosis (Wang et al., 2010). At present, heparin is a commonly used anticoagulant, but it has some negative effects, such as thrombocytopenia and spontaneous bleeding (Tardy-Poncet et al., 1994). Therefore, searching for a substitute with fewer side effects than heparin drugs is required.

Sargussum fusiforme belongs to the Sargassaceae, an economically valuable algae widely distributed in coastal areas of China, Japan, and Korea (Zhang et al., 2002). To meet the huge market demand, S. fusiforme is being cultivated in Chinese coastal regions at large scale, accounting for 2.6% (2 482 ha) of the total cultivation area of China's economic seaweeds. In addition to wild harvests, cultivated production has reached 32 000 t (fresh wt; Qian et al., 2016).

Sargussum fusiforme is rich in protein, polysaccharides, and trace elements. Polysaccharides often contain abundant fucose and galactose residues as well as some mannose, glucose, glucuronic acid, and xylose (Hu et al., 2016). Sargussum fusiforme polysaccharides (SFP) feature many biological and pharmacological functions, acting as antitumor, antiviral, or antioxidant agents for immune enhancement (Chen et al., 2012, 2016, 2017; Guo et al., 2014). Its anticoagulant effects have recently received wide attention. Kim et al. (1998) have reported that sulfated SFP carries anticoagulant activity. Zhang et al. (2008) have reported good anticoagulant activity by SFP in vitro and in vivo as well as obvious inhibition effects against intrinsic coagulation. Liu et al. (2004) have obtained anticoagulant components from S. fusiforme aqueous extractions from which a sulfated polysaccharide was determined and the compound's anticoagulant activity related to its total sugar and fucose content. In recent years, many studies have found that the effects of low molecular weight (MW) seaweed polysaccharides on immunomodulation, antitumor, antithrombosis, and antioxidation were better than high MW polysaccharides (Sun et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2016). At present, research on anticoagulant activities of low MW S. fusiforme polysaccharides (LSFP) has been scarce. This study was conducted to prepare LSFP from S. fusiforme via H2O2 oxidative degradation, to determine the progress of SFP degradation under different conditions, including temperature, pH, and H2O2 concentration, and finally, to explore the relationships between SFP and LSFP anticoagulant activity and polysaccharide MW. The results of this research might provide a theoretical basis for the development of LSFP clinical applications for thrombosis treatments.

2 MATERIAL AND METHOD 2.1 Extraction of SFPSargassum fusiform was purchased from Rongcheng Xufeng Aquatic Products Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China). The fresh seaweed was washed with distilled water, dried at 50℃ to a constant weight, ground and crushed to pass through a 60-mesh sieve, and stored at room temperature for later use. All reagents were analytical grade. Traditional hot water extraction and alcohol precipitation methods (Song et al., 2016) were used with modifications. Briefly, a 30-fold volume of distilled water was mixed with the algae powder at 70℃, stirred for 4 h, and filtered after cooling to room temperature. The filtrate was concentrated to 1/4 volume by a rotary evaporator, 10 mol/L HCl added to adjust the pH to 2, and centrifuged at 8 000 r/min for 5 min. The supernatant was then dialyzed to remove salt for ~2 d, condensed again to 1/4 volume, and a 3-fold volume of anhydrous ethanol added to precipitate the polysaccharides. The sediment and supernatant were stored overnight at 4℃, centrifuged at 8 000 r/min for 5 min, and the precipitate freeze-dried for use in obtaining SFP.

2.2 Chemical characterizationTotal sugar was analyzed using the phenol-sulfuric acid method (Dubois et al., 1956). Sulfated content was measured using a barium chloride gelatin method (Kawai et al., 1969). The MW was determined by high performance gel permeation chromatography (HPGPC) with 0.1 mol/L Na2SO4 used as the mobile phase on an Agilent 1260 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Dextran standards of 1 000, 5 000, 12 000, 50 000, 80 000, 270 000, and 670 000 Da (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO USA) were used to calibrate the column. Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopic (FT-IR) spectra of samples were recorded from SFP and LSFP samples in KBr pellets on a Nicolet-360 FT-IR spectrometer (Nicolet Instrument Corp., Madison, WI, USA) and with detection from 400 to 4 000/cm.

2.3 Influence of H2O2 oxidation on SFP degradation and LSFP preparationA 0.8-g sample of the freeze-dried product was dissolved in 40 mL of distilled water, H2O2 solution added, and heated in a water bath. The degradation product MW in the reaction liquid were sampled and analyzed by HPGPC every 30 min to investigate the effects of temperature (60, 70, 80, 90, and 100℃), pH (1, 2, 3, 4, and 8), and H2O2 concentration (0.15%, 0.3%, 1.5%, 3%, and 4.5%, by vol) on the degradation. Several LSFPs were prepared in greater mass under different degradation conditions.

2.4 Anticoagulant activity in vitroAn assay kit for activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) was purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Inst. (Nanjing, China; Kit No. F008- 1). In this assay, 0.05 mL of plasma samples were mixed with 0.05 mL SFP or LSFP (predissolved in 0.9% NaCl solution), warmed at 37℃ for 60 s, then 0.05 mL of prewarmed APTT reagent added, and the mixture incubated at 37℃ for 3 min. Subsequently, 0.05 mL of prewarmed 0.025 mol/L CaCl2 solution was added and the APTT recorded by a HF6000-4 semi-automatic blood coagulation analyzer (Han Fang Medical Instrument Co., Ltd., Shandong, China). Heparin and 0.9% NaCl solutions were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

An assay kit for prothrombin time (PT) was purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Inst. (Kit No. F007). In this assay, 0.05 mL of sample solutions were mixed with 0.05 mL of plasma, and incubated at 37℃ for 3 min. Then, 0.1 mL of prewarmed PT reagent was added and the PT recorded using the blood coagulation analyzer. Heparin and 0.9% NaCl solutions were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

An assay kit for thrombin time (TT) was also purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Inst. (Kit No. F009). Using SFP or other LSFPs solutions at different concentrations, 0.5 mL volumes were mixed with 0.1 mL of plasma and incubated at 37℃ for 3 min. Immediately, 0.1 mL of prewarmed TT regent was added and the TT recorded using the blood coagulation analyzer. Heparin and 0.9% NaCl solutions were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

2.5 Data analysis methodStatistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Version 21.0). The effects of SFP and LSFP on APTT, PT, and TT were determined by one-way ANOVA.

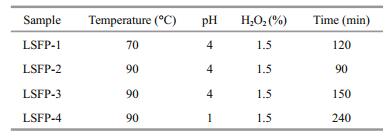

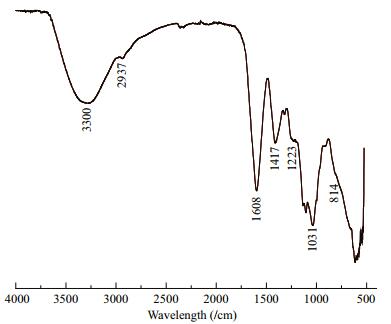

3 RESULT 3.1 FT-IR spectra characterizationAn FT-IR spectrum of SFP is shown in Fig. 1. According to previous reports (Wang et al., 2007; Bouhlal et al., 2011; Camara et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2011), the absorption peaks at 3 300/cm represented O-H stretching vibrations and that at 2 937/cm indicated C-H stretching vibrations. Two absorption peaks at 1 608 and 1 417/cm corresponded to asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of C=O, respectively. S=O stretching vibrations appeared at 1 223/cm, and the C-O-H deformation vibrations at 1 031/cm. The tiny-peak at 814/cm reflected C-O-S-symmetry stretching vibrations. The pattern described here showed that the obtained SFP was typical sulfated polysaccharides.

|

| Figure 1 FTIR spectrum of SFP |

The effects of pH, temperature, and H2O2 concentration on the degradation process were examined and the results shown below.

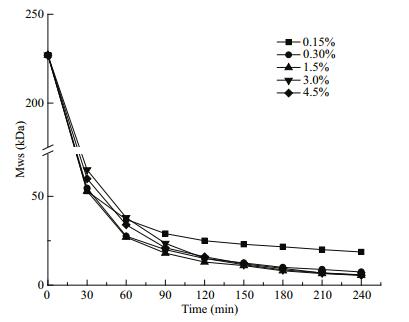

The effects on polysaccharide MW from degradation with H2O2 concentrations from 0.15 to 4.5% (by vol) were examined with pH 4 and 80℃ constant (Fig. 2). In the first 90 min, reactions were rapid and similar in all H2O2 concentration groups and, when the MW decreased to ~25 kDa, degradation slowed down. The 0.15% H2O2 group stood out from the others after 90 min, with significantly slowed degradation rates, with a MW of only 18.7 kDa at 240 min. Other MWs were 7.4, 5.5, 5.8, and 5.6 kDa with 0.3%, 1.5%, 3.0%, and 4.5% H2O2, respectively. Consequently, 1.5% H2O2 was chosen for later reactions.

|

| Figure 2 Effects of H2O2 concentration on molecule weight of SFP |

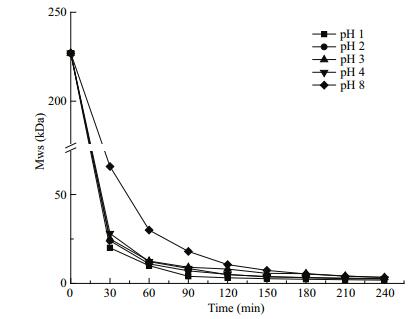

The impacts of acidity on the MW at a pH of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8 were determined at 80℃ and 1.5% H2O2 (Fig. 3). As pH decreased from 8 to 1, the resulting MW increased. After 30 min, the MW was 65.8, 28.1, 25, 24, and 20 kDa at pH 8, 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively. Beyond the 90 min point, similar to curves in Fig. 2, the MW changed slightly and remained constant. LSFP (~2.5 kDa) of similar MW were obtained at 240 min, which was explained by the belief that acidity greatly affected the formation rate of free radicals. In acidic conditions (pH≤4), the radical releasing rates were greater and similar, such that degradation rates were greater and degradation curves more similar. In an alkaline condition (pH=8), the MW was higher in the early stages because of low free radical generation. When the MW became low and products were difficult to further degrade, the degradation efficiency also became low.

|

| Figure 3 Effect of acidity on molecule weight of SFP |

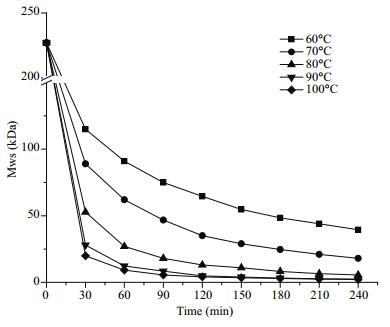

Temperature impacts on polysaccharide breakdown were examined for 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100℃ and at a constant pH 4 and 1.5% H2O2 (Fig. 4). There was a clear impact by temperature, such that, among all groups, those of 90 and 100℃ reacted faster and showed nearly the same rate of MW reduction at 28 and 19.9 kDa in 30 min, and 4.9 and 4.1 kDa in 120 min, respectively. However, at 60, 70, and 80℃, the MW decreased to 64.6, 35, and 13 kDa in 120 min, respectively. The final MW at 90 and 100℃ were 2.4 and 2.1 kDa, respectively, which was remarkably lower than those from the other three temperatures. Although the MW from 60, 70, and 80℃ at 240 min were greater, they might be degraded further with longer reaction times. Therefore, LSFP might have been prepared at low temperature with prolonged degradation time, but an extremely long reaction time was not realistic. Thus, it was more feasible to generate low MW polysaccharides at a higher temperature.

|

| Figure 4 Effect of temperature on molecule weight of SFP |

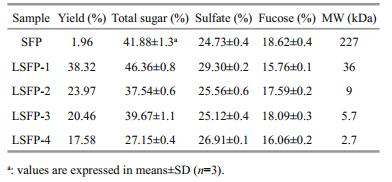

According to the results in Section 3.2, four LSFP were prepared under different conditions (Table 1), and their chemical compositions and that of the SFP analyzed (Table 2). The SFP %-yield (dry wt) was calculated by the ratio of SFP to the starting S. fusiforme dry wt (0.8 g) and the LSFP %-yields were calculated from the LSFP to SFP ratio. The results showed that the LSFP yield decreased as MW decreased. In addition, the trends of variation in total sugar content and MW were similar. However, the sulfated content of LSFP-1 was 29.3% higher than the others.

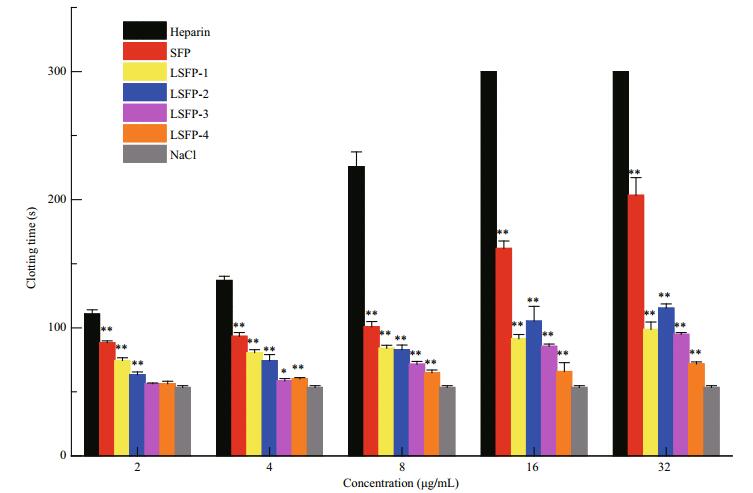

Coagulation pathways are categorized into intrinsic, extrinsic, and common coagulation pathways. The coagulation factors involved in intrinsic pathway all derive from blood. However, not all coagulation factors participating in an extrinsic coagulant pathway come from blood. The common coagulation pathway encompasses a stage from the activation of coagulation factors to fibrin formation, which is a joint approach of the intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways (Wang et al., 2013). APTT is the most commonly used screening test for the intrinsic coagulation pathway in vitro. Compared with NaCl, all samples prolonged the APTT significantly in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5). At 32 μg/mL, SFP exhibited the greatest anticoagulation effects, with APTT results at 203.5, which was much smaller than heparin (> 300 s). The clotting time of LSFP-2 was 105 and 115 s at concentrations of 16 and 32 μg/mL, respectively; while those of LSFP-1 were 91.6 and 98.8 s, respectively, which showed that LSFP-2 was slightly more effective than LSFP-1. Nonetheless, in general, anticoagulant effects decreased as MW decreased at the same concentration, which illustrated that samples of greater MW had stronger interactions with intrinsic coagulation factors (Melo et al., 2004).

|

| Figure 5 Anticoagulant activity of SFP and LSFP measured in APTT assay Significance: *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01, higher than NaCl. |

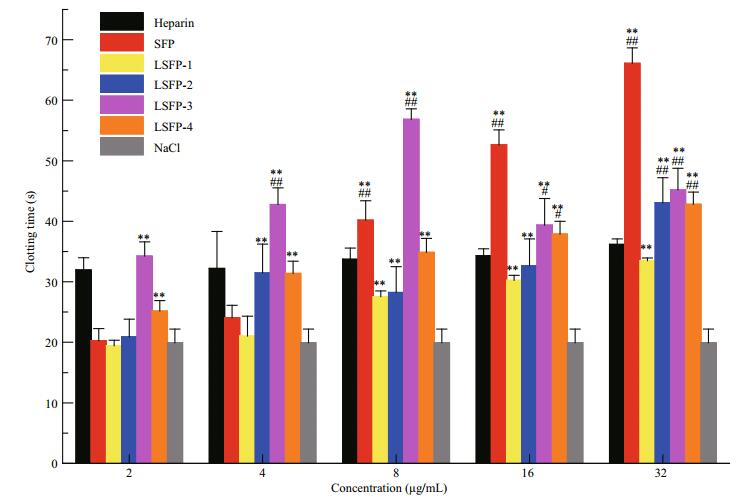

PT is defined as the time required for conversion from prothrombin to thrombin after the addition of excess tissue factor into plasma and is used to reflect the status of blood coagulation in medical science. SFP and some LSFP did not exhibit anticoagulant activity at low concentrations, at 2 and 4 μg/mL (Fig. 6). For LSFP-3, among all tested concentrations, the 8 μg/mL group showed the greatest effect, with a clotting time of 56 s, indicating the optimal concentration. In addition to LSFP-3, SFP and the other LSFPs at 8, 16, and 32 μg/mL prolonged PT times and the results positively correlated with sample concentration. LSFP-1 showed the least anticoagulant activity with a PT of 33.5 s at 32 μg/mL; meanwhile, SFP showed the highest activity, at 66 s. However, correlation between anticoagulant activity and MW was complicated, in that it was speculated that these results might have resulted from a combination of effects, jointly contributed by sulfate percentage, molecular weight, and monosaccharide composition.

|

| Figure 6 Anticoagulant activity of SFP and LSFP measured in PT assay Significance: *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01, higher than NaCl; #: P < 0.05; ##: P < 0.01, higher than heparin. |

TT refers to the time of blood coagulation with a standardized thrombin addition into plasma, and it is used to evaluate the capability of converting thrombin and plasma fibrinogen into fibrin, often considered as an indicator for common coagulant pathways. TT assay results on samples indicated that all samples remarkably extended TT times, implying that SFP and LSFP inhibited polymerization of thrombin and fibrinogen (Fig. 7). With decreased MW, TT times exhibited a decreasing trend. Among all samples, LSFP-1, with the least effects in PT assay, showed the greatest effects on TT, reaching 59 s at 32 μg/mL. SFP also possessed greater activity in TT assay, showing 53 s at 32 μg/mL, second only to LSFP-1, while the positive control heparin was just 44 s. Overall, with increased concentration, enhancements in anticoagulant effects were not obvious.

|

| Figure 7 Anticoagulant activity of SFP and LSFP measured in TT assay Significance: *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01, higher than NaCl; #: P < 0.05; ##: P < 0.01, higher than heparin. |

In this paper, SFP of 227 kDa were obtained from S. fusiforme and because its high MW influenced its aqueous solubility and biological activities, it was necessary to degrade these polysaccharides to increase solubility and activity. As H2O2 oxidative degradation is a popular and efficient method for polysaccharide degradation and unreacted H2O2 is easily removed, this method was applied to degrade SFP to form lower MW LSPF. In addition, the MW effects of temperature, acidity, and H2O2 concentration on SFP degradation were examined, and several different, representative LSFP were prepared. The results showed that the degradation rate was positively related to temperature (60–100℃) and H2O2 concentration (0.15%–4.5%) and negatively to pH (1–8). During degradation, H2O2 produced active free radicals, e.g., HOO-, ·O2ˉ, and HO·, and then these radicals broke glycosidic linkages with unpaired electrons (Hou et al., 2012). More concentrated H2O2 could produce more free radicals and might have caused a greater degradation rate, but in this study, the MW of final products were nearly the same when the H2O2 concentration was 1.5% and above. Therefore, 1.5% was sufficient for SFP degradation. More free radicals did not contribute to degradation after the MW had decreased to 5 kDa. Energy to break up glycosidic linkages might be gained with higher temperature or lower pH, which would then generate lower-MW products.

The pH of the reaction mixture affected the free radical generation efficiency and thus altered the degradation rate. Therefore, pH was a critical factor for SFP degradation. Li et al. (2013) have shown that HCl at different concentrations significantly affects polysaccharide degradation. With 0.1 mol/L HCl (pH 1), the MW of degraded polysaccharides reached 1 kDa after 60 min of reaction. However, at 0.01 mol/L HCl (pH 2), the MW was ~200 kDa by the same time. In this study, pH had clear effects on the MW of degraded polysaccharides, and thus, a relatively low pH was beneficial to polysaccharide degradation. In contrast, the degradation rate at pH 8 was much smaller than at other pHs (pH 1, 2, 3, and 4), which was probably due to slow free radical generation under alkaline conditions. In the four acidic groups (pH 1, 2, 3, and 4), although lower pH increased the degradation rate in the first 120 min, intergroup differences were not obvious at later times. Therefore, pH 4 was judged sufficient for polysaccharide degradation. Also, a pH lower than 4 might cause side effects in polysaccharide degradation. In LSFP-4 preparations, at pH 1, the total sugar content was significantly lower than the other LSFP (Table 2), indicating that, at a very low pH (e.g., pH 1), sugar units could be disrupted. Thus, as acidity was important in polysaccharide degradation, a medium pH condition was considered more appropriate for the present subsequent degradations.

Temperature was another important factor. A higher temperature means greater kinetic energy in all constituent molecules (Yue et al., 2008), and stronger collisions among free radicals and carbohydrate chains, thus affecting free radical formation. Therefore, temperature increases would boost a reaction. In the present case, with increased temperature, degradation rates increased significantly and showed a certain change in gradient. However, at 90 and 100℃, no significant differences were observed and the reaction results were similar, indicating that, at 90℃, the reaction mixture had sufficient energy to facilitate and support the reaction. In addition, higher temperatures could destroy sugar units and decompose H2O2 (Hou et al., 2012). Therefore, 90℃ was set as the upper temperature limit in subsequent preparations.

Based on the results of the above sets of experiments, different conditions were set to prepare different LSFP (MW 36, 9, 5.7, and 2.7 kDa for LSFP-1, LSFP-2, LSFP-3, and LSFP-4, respectively; Tables 1 and 2) and their anticoagulant activities studied. The APTT assay, to determine the effects of SFP and LSFPs on intrinsic factors, such as Ⅶ, Ⅸ, Ⅺ, and Ⅻ, showed that the clotting time was prolonged in all samples. Moreover, the anticoagulant activity of samples increased with increased concentration. SFP (sulfate 24.73%, MW 227 kDa) showed the highest anticoagulant activity, indicating that SFP features a suitable molecular structure for interacting with intrinsic factors to prevent blood clotting (Wang et al., 2010). Similarly, in TT assay, all samples presented anticoagulant activity, with some performing better than heparin. Therefore, some of these polysaccharides inhibited thrombin or fibrin polymerization to prevent blood clotting (Wang, 2010). On the other hand, anticoagulant activity correlated with MW except for LSFP-1. The clotting time of LSFP-1 was slightly longer than those of other LSFPs, indicating that sulfate content (29.3% for LSFP-1) was another factor in TT assay. Overall, among all samples, anticoagulant activity related positively with MW and sulfate content in APTT and TT assays. These results were similar to observations reported by Jin et al. (2013), who have found that the galactose/fucose molar ratio and MW affect the anticoagulant activity of 11 fucoidans (MW 90.1–8.4 kDa) in APTT and TT assays. In addition, Chandía and Matsuhiro (2008), who has reported that a native fucoidan (MW 320 kDa) from Lessonia vadosa shows better anticoagulant activity than that of a radical depolymerized fraction (MW 32 kDa) in TT assay. These findings were coincident with the present results, but the MW range of the present samples was wider (MW 227–2.7 kDa). In addition, as the MW of LSFP-4 was only 2.7 kDa, which qualified as an oligosaccharide, SFP was considered here to be better in anticoagulant activity than oligosaccharides of S.fusiforme. For this mechanism, these polysaccharides were inferred to bind with coagulation factors and inhibit thrombin activity or fibrin polymerization, which play important roles in the intrinsic and common pathways. SFP (in higher MW) featured a special molecular structure that was able to retard the coagulation process, unlike a lower-MW polysaccharide that, with a lesser structure, exerted weaker inhibition. In PT assay of all samples, clotting times were lengthened and the anticoagulant activity showed a positive relationship with a sample's concentration. However, LSFP-3 in medium concentration (8 μg/mL, Fig. 7) exhibited a stronger anticoagulant effect, which appeared to be the optimal LSFP-3 concentration. LSFP-1 possessed a higher MW and the highest sulfate and total sugar contents but showed the least anticoagulant effects. It appeared that PT results were not related to MW or sulfate alone and that fucose content was another important factor. SFP and LSFP-3, with higher fucose contents, exerted higher anticoagulant activity, while LSFP-1 had the lowest fucose content and exhibited the least. As has been found by Cheng and Wu (2011), fucoidan extracted from S. fusiforme affected APTT and TT but not PT, and some other polysaccharides or low-MW polysaccharides isolated from different algae also show no inhibition on PT (Sudharsan et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017). In this study, all tested samples influenced APTT, TT, and PT, but different configurations of polymer molecules presented different effects. The anticoagulant activity of these polysaccharides was not only related to MW, sulfate, and fucose content but also to their molecular structure, on which more studies will be conducted. In addition, SFP and LSFP not only influenced the intrinsic and common coagulation pathways but also inhibited the extrinsic pathway, a finding that might improve the usage of SFP and LSFP in anticoagulant therapies. Their medical applications should be developed, expanded, and promoted in the future.

5 CONCLUSIONThis study demonstrated that H2O2 oxidative degradation was an effective means for degrading SFP. The degradation rate was positively related to temperature (60–100℃), H2O2 concentration (0.15%– 4.5%) and negatively to pH (1–8). From SFP, four LSFP were prepared by the H2O2 degradation method to investigate the relationship between MW and anticoagulant activity. The results showed that MW affected APTT and TT and that fucose content influenced PT, which indicated that the MW had an impact on the intrinsic and common pathways but not the extrinsic pathway. However, other factors, such as the content and position of sulfate, the function of substituent groups, and the carbohydrate skeletal structure could also have affected and complicated the results. The major factors and mechanism involved in these anticoagulant activities remain undetermined, which will be elucidated in the future.

6 DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENTThe original data that support the findings of this article are available from the corresponding author Li upon reasonable request. As the data are under the duration of patent protection, the data are not publicly available.

Bouhlal R, Haslin C, Chermann J C, Colliec-Jouault S, Sinquin C, Simon G, Cerantola S, Riadi H, Bourgougnon N. 2011. Antiviral activities of sulfated polysaccharides isolated from Sphaerococcus coronopifolius (Rhodophytha, Gigartinales) and Boergeseniella thuyoides (Rhodophyta, Ceramiales). Marine Drugs, 9(12): 1 187-1 209. |

Camara R B G, Costa L S, Fidelis G P, Nobre L T D B, DantasSantos N, Cordeiro S L, Costa M S S P, Alves L G, Rocha H A O. 2011. Heterofucans from the brown seaweed Canistrocarpus cervicornis with anticoagulant and antioxidant activities. Marine Drugs, 9(1): 124-138. DOI:10.3390/md9010124 |

Chandía N P, Matsuhiro B. 2008. Characterization of a fucoidan from Lessonia vadosa (Phaeophyta) and its anticoagulant and elicitor properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 42(3): 235-240. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2007.10.023 |

Chen B J, Shi M J, Cui S, Hao S X, Hider R C, Zhou T. 2016. Improved antioxidant and anti-tyrosinase activity of polysaccharide from Sargassum fusiforme by degradation. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 92: 715-722. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.07.082 |

Chen H L, Zhang L, Long X E, Li P F, Chen S C, Kuang W, Guo J M. 2017. Sargassum fusiforme polysaccharides inhibit VEGF-A-related angiogenesis and proliferation of lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 85: 22-27. |

Chen S G, Xue C H, Yin L A, Tang Q J, Yu G L, Chai W G. 2011. Comparison of structures and anticoagulant activities of fucosylated chondroitin sulfates from different sea cucumbers. Carbohydrate Polymers, 83(2): 688-696. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.08.040 |

Chen X M, Nie W J, Yu G Q, Li Y L, Hu Y S, Lu J X, Jin L Q. 2012. Antitumor and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from Sargassum fusiforme. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 50(3-4): 695-700. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2011.11.015 |

Cheng Z L, Wu X N. 2011. Study on the anticoagulant activities and promoting effect on human umbilical vein endothelial cells proliferation activity of fucoidan from Sargassum fusiforme Setchel. Food Research and Development, 32(4): 165-167. |

Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F. 1956. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical Chemistry, 28(3): 350-356. DOI:10.1021/ac60111a017 |

Guo H J, Liu Y Z, Paskaleva E E, Arra M, Kennedy J S, Shekhtman A, Canki M. 2014. Use of Sargassum fusiforme extract and its bioactive molecules to inhibit HIV infection:bridging two paradigms between eastern and western medicine. Chinese Herbal Medicines, 6(4): 265-273. DOI:10.1016/S1674-6384(14)60041-1 |

Hou Y, Wang J, Jin W H, Zhang H, Zhang Q B. 2012. Degradation of Laminaria japonica fucoidan by hydrogen peroxide and antioxidant activities of the degradation products of different molecular weights. Carbohydrate Polymers, 87(1): 153-159. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.07.031 |

Hu P, Li Z X, Chen M C, Sun Z L, Ling Y, Jiang J, Huang C G. 2016. Structural elucidation and protective role of a polysaccharide from Sargassum fusiforme on ameliorating learning and memory deficiencies in mice. Carbohydrate Polymers, 139: 150-158. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.12.019 |

Jin W H, Zhang Q B, Wang J, Zhang W J. 2013. A comparative study of the anticoagulant activities of eleven fucoidans. Carbohydrate Polymers, 91(1): 1-6. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.07.067 |

Kawai Y, Seno N, Anno K. 1969. A modified method for chondrosulfatase assay. Analytical Biochemistry, 32(2): 314-321. DOI:10.1016/0003-2697(69)90091-8 |

Kim K I, Seo H D, Lee H S, Jo H Y, Yang H C. 1998. Studies on the blood anticoagulant polysaccharide isolated from hot water extracts of Hizikia fusiforme. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition, 27(6): 1 204-1 210. |

Li B, Liu S, Xing R E, Li K C, Li R F, Qin Y K, Wang X Q, Wei Z H, Li P C. 2013. Degradation of sulfated polysaccharides from Enteromorpha prolifera and their antioxidant activities. Carbohydrate Polymers, 92(2): 1 991-1 996. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.11.088 |

Li N, Liu X, He X X, Wang S Y, Cao S J, Xia Z, Xian H L, Qin L, Mao W J. 2017. Structure and anticoagulant property of a sulfated polysaccharide isolated from the green seaweed Monostroma angicava. Carbohydrate Polymers, 159: 195-206. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.12.013 |

Liu C C, Zhou Y, Wu Y R, Gan J H, Zhou P G. 2004. Screening of the components with blood-anticoagulant activity from marine algae Sargassum fusiforme and Undaria pinnatifida. Journal of Fisheries of China, 28(4): 473-476. |

Melo F R, Pereira M S, Foguel D, Mourão P A S. 2004. Antithrombin-mediated anticoagulant activity of sulfated polysaccharides:different mechanisms for heparin and sulfated galactans. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 279(20): 20 824-20 835. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M308688200 |

Pang X X, Wang X. 2011. Research progress in tthrombosis and its mechanism. Medical Recapitulate, 17(11): 1 613-1 616. |

Qian W G, Li N, Lin L D, Xu T, Zhang X, Wang L H, Zou H X, Wu M J, Yan X F. 2016. Parallel analysis of proteins in brown seaweed Sargassum fusiforme responding to hyposalinity stress. Aquaculture, 465: 189-197. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.08.032 |

Song L, Chen X L, Liu X D, Zhang F B, Hu L F, Yue Y, Li K C, Li P C. 2016. Characterization and comparison of the structural features, immune-modulatory and anti-avian influenza virus activities conferred by three algal sulfated polysaccharides. Marine Drugs, 14(1): 4. |

Sudharsan S, Subhapradha N, Seedevi P, Shanmugam V, Madeswaran P, Shanmugam A, Srinivasan A. 2015. Antioxidant and anticoagulant activity of sulfated polysaccharide from Gracilaria debilis (Forsskal). International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 81: 1 031-1 038. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.09.046 |

Sun L Q, Wang L, Zhou Y. 2012. Immunomodulation and antitumor activities of different-molecular-weight polysaccharides from Porphyridium cruentum. Carbohydrate Polymers, 87(2): 1 206-1 210. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.08.097 |

Tardy-Poncet B, Tardy B, Grelac F, Reynaud J, Mismetti P, Bertrand J C, Guyotat D. 1994. Pentosan polysulfateinduced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis. American Journal of Hematology, 45(3): 252-257. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1096-8652 |

Wang J, Zhang Q B, Zhang Z S, Song H F, Li P C. 2010. Potential antioxidant and anticoagulant capacity of low molecular weight fucoidan fractions extracted from Laminaria japonica. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 46(1): 6-12. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.10.015 |

Wang J. 2010. Study on the Structure, Derivatives and Activities of Fucoidan Extracted from Laminia Japonica. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Institute of Oceanography), Beijing, China. p. 75-76. (in Chinese with English abstract)

|

Wang N, Feng Y F, Fan H P, Ma L, Wang D L, Wang D L, Ai Z L. 2013. Study on the difference of anticoagulant activity in vitro of crude polysaccharide of Jujube. Journal of Chinese Institute of Food Science and Technology, 13(12): 34-39. |

Wang S C, Bligh S W A, Shi S S, Wang Z T, Hu Z B, Crowder J, Branford-White C, Vella C. 2007. Structural features and anti-HIV-1 activity of novel polysaccharides from red algae Grateloupia longifolia and Grateloupia filicina. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 41(4): 369-375. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2007.05.008 |

Yue W, Yao P J, Wei Y A, Li S Q, Lai F, Liu X M. 2008. An innovative method for preparation of acid-free-watersoluble low-molecular-weight chitosan (AFWSLMWC). Food Chemistry, 108(3): 1 082-1 087. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.11.047 |

Zhang Z E, Liu X L, Yang J Y, Liu C C. 2008. Study on anticoagulant activity of sulfated polysaccharides from Hizikia fusiformis. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences, 36(18): 7 505-7 508, 7 542. |

Zhang Z, Liu J G, Liu J D. 2002. Study review of Hizikia fusiformis. Marine Fisheries Research, 23(3): 67-74. |

Zhao X, Guo F J, Hu J, Zhang L J, Xue C H, Zhang Z H, Li B F. 2016. Antithrombotic activity of oral administered low molecular weight fucoidan from Laminaria japonica. Thrombosis Research, 144: 46-52. DOI:10.1016/j.thromres.2016.03.008 |

| Bouhlal R, Haslin C, Chermann J C, Colliec-Jouault S, Sinquin C, Simon G, Cerantola S, Riadi H, Bourgougnon N, 2011. Antiviral activities of sulfated polysaccharides isolated from Sphaerococcus coronopifolius (Rhodophytha, Gigartinales) and Boergeseniella thuyoides (Rhodophyta, Ceramiales). Marine Drugs, 9(12): 1 187–1 209. |

| Camara R B G, Costa L S, Fidelis G P, Nobre L T D B, DantasSantos N, Cordeiro S L, Costa M S S P, Alves L G, Rocha H A O, 2011. Heterofucans from the brown seaweed Canistrocarpus cervicornis with anticoagulant and antioxidant activities. Marine Drugs, 9(1): 124–138. Doi: 10.3390/md9010124 |

| Chandía N P, Matsuhiro B, 2008. Characterization of a fucoidan from Lessonia vadosa (Phaeophyta) and its anticoagulant and elicitor properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 42(3): 235–240. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2007.10.023 |

| Chen B J, Shi M J, Cui S, Hao S X, Hider R C, Zhou T, 2016. Improved antioxidant and anti-tyrosinase activity of polysaccharide from Sargassum fusiforme by degradation. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 92: 715–722. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.07.082 |

| Chen H L, Zhang L, Long X E, Li P F, Chen S C, Kuang W, Guo J M, 2017. Sargassum fusiforme polysaccharides inhibit VEGF-A-related angiogenesis and proliferation of lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 85: 22–27. |

| Chen S G, Xue C H, Yin L A, Tang Q J, Yu G L, Chai W G, 2011. Comparison of structures and anticoagulant activities of fucosylated chondroitin sulfates from different sea cucumbers. Carbohydrate Polymers, 83(2): 688–696. Doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.08.040 |

| Chen X M, Nie W J, Yu G Q, Li Y L, Hu Y S, Lu J X, Jin L Q, 2012. Antitumor and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from Sargassum fusiforme. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 50(3-4): 695–700. Doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.11.015 |

| Cheng Z L, Wu X N, 2011. Study on the anticoagulant activities and promoting effect on human umbilical vein endothelial cells proliferation activity of fucoidan from Sargassum fusiforme Setchel. Food Research and Development, 32(4): 165–167. |

| Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F, 1956. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical Chemistry, 28(3): 350–356. Doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017 |

| Guo H J, Liu Y Z, Paskaleva E E, Arra M, Kennedy J S, Shekhtman A, Canki M, 2014. Use of Sargassum fusiforme extract and its bioactive molecules to inhibit HIV infection:bridging two paradigms between eastern and western medicine. Chinese Herbal Medicines, 6(4): 265–273. Doi: 10.1016/S1674-6384(14)60041-1 |

| Hou Y, Wang J, Jin W H, Zhang H, Zhang Q B, 2012. Degradation of Laminaria japonica fucoidan by hydrogen peroxide and antioxidant activities of the degradation products of different molecular weights. Carbohydrate Polymers, 87(1): 153–159. Doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.07.031 |

| Hu P, Li Z X, Chen M C, Sun Z L, Ling Y, Jiang J, Huang C G, 2016. Structural elucidation and protective role of a polysaccharide from Sargassum fusiforme on ameliorating learning and memory deficiencies in mice. Carbohydrate Polymers, 139: 150–158. Doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.12.019 |

| Jin W H, Zhang Q B, Wang J, Zhang W J, 2013. A comparative study of the anticoagulant activities of eleven fucoidans. Carbohydrate Polymers, 91(1): 1–6. Doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.07.067 |

| Kawai Y, Seno N, Anno K, 1969. A modified method for chondrosulfatase assay. Analytical Biochemistry, 32(2): 314–321. Doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90091-8 |

| Kim K I, Seo H D, Lee H S, Jo H Y, Yang H C, 1998. Studies on the blood anticoagulant polysaccharide isolated from hot water extracts of Hizikia fusiforme. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition, 27(6): 1 204–1 210. |

| Li B, Liu S, Xing R E, Li K C, Li R F, Qin Y K, Wang X Q, Wei Z H, Li P C, 2013. Degradation of sulfated polysaccharides from Enteromorpha prolifera and their antioxidant activities. Carbohydrate Polymers, 92(2): 1 991–1 996. Doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.11.088 |

| Li N, Liu X, He X X, Wang S Y, Cao S J, Xia Z, Xian H L, Qin L, Mao W J, 2017. Structure and anticoagulant property of a sulfated polysaccharide isolated from the green seaweed Monostroma angicava. Carbohydrate Polymers, 159: 195–206. Doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.12.013 |

| Liu C C, Zhou Y, Wu Y R, Gan J H, Zhou P G, 2004. Screening of the components with blood-anticoagulant activity from marine algae Sargassum fusiforme and Undaria pinnatifida. Journal of Fisheries of China, 28(4): 473–476. |

| Melo F R, Pereira M S, Foguel D, Mourão P A S, 2004. Antithrombin-mediated anticoagulant activity of sulfated polysaccharides:different mechanisms for heparin and sulfated galactans. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 279(20): 20 824–20 835. Doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308688200 |

| Pang X X, Wang X, 2011. Research progress in tthrombosis and its mechanism. Medical Recapitulate, 17(11): 1 613–1 616. |

| Qian W G, Li N, Lin L D, Xu T, Zhang X, Wang L H, Zou H X, Wu M J, Yan X F, 2016. Parallel analysis of proteins in brown seaweed Sargassum fusiforme responding to hyposalinity stress. Aquaculture, 465: 189–197. Doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.08.032 |

| Song L, Chen X L, Liu X D, Zhang F B, Hu L F, Yue Y, Li K C, Li P C, 2016. Characterization and comparison of the structural features, immune-modulatory and anti-avian influenza virus activities conferred by three algal sulfated polysaccharides. Marine Drugs, 14(1): 4. |

| Sudharsan S, Subhapradha N, Seedevi P, Shanmugam V, Madeswaran P, Shanmugam A, Srinivasan A, 2015. Antioxidant and anticoagulant activity of sulfated polysaccharide from Gracilaria debilis (Forsskal). International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 81: 1 031–1 038. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.09.046 |

| Sun L Q, Wang L, Zhou Y, 2012. Immunomodulation and antitumor activities of different-molecular-weight polysaccharides from Porphyridium cruentum. Carbohydrate Polymers, 87(2): 1 206–1 210. Doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.08.097 |

| Tardy-Poncet B, Tardy B, Grelac F, Reynaud J, Mismetti P, Bertrand J C, Guyotat D, 1994. Pentosan polysulfateinduced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis. American Journal of Hematology, 45(3): 252–257. Doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1096-8652 |

| Wang J, Zhang Q B, Zhang Z S, Song H F, Li P C, 2010. Potential antioxidant and anticoagulant capacity of low molecular weight fucoidan fractions extracted from Laminaria japonica. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 46(1): 6–12. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.10.015 |

| Wang J. 2010. Study on the Structure, Derivatives and Activities of Fucoidan Extracted from Laminia Japonica. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Institute of Oceanography), Beijing, China. p. 75-76. (in Chinese with English abstract) |

| Wang N, Feng Y F, Fan H P, Ma L, Wang D L, Wang D L, Ai Z L, 2013. Study on the difference of anticoagulant activity in vitro of crude polysaccharide of Jujube. Journal of Chinese Institute of Food Science and Technology, 13(12): 34–39. |

| Wang S C, Bligh S W A, Shi S S, Wang Z T, Hu Z B, Crowder J, Branford-White C, Vella C, 2007. Structural features and anti-HIV-1 activity of novel polysaccharides from red algae Grateloupia longifolia and Grateloupia filicina. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 41(4): 369–375. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2007.05.008 |

| Yue W, Yao P J, Wei Y A, Li S Q, Lai F, Liu X M, 2008. An innovative method for preparation of acid-free-watersoluble low-molecular-weight chitosan (AFWSLMWC). Food Chemistry, 108(3): 1 082–1 087. Doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.11.047 |

| Zhang Z E, Liu X L, Yang J Y, Liu C C, 2008. Study on anticoagulant activity of sulfated polysaccharides from Hizikia fusiformis. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences, 36(18): 7 505–7 508, 7 542. |

| Zhang Z, Liu J G, Liu J D, 2002. Study review of Hizikia fusiformis. Marine Fisheries Research, 23(3): 67–74. |

| Zhao X, Guo F J, Hu J, Zhang L J, Xue C H, Zhang Z H, Li B F, 2016. Antithrombotic activity of oral administered low molecular weight fucoidan from Laminaria japonica. Thrombosis Research, 144: 46–52. Doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.03.008 |

2018, Vol. 36

2018, Vol. 36